Fight School Drop Out in Shan State, Myanmar

The current situation in Myanmar is more than complex – ethnic minorities are torn between a political crisis, increasing poverty, drug and human trafficking […]

On the 28th of January 2020, in Lashio, a large Shan-state town in the northeast of Myanmar, some 6000 people have gathered to celebrate the appointing of the new bishop. Over four days of prayers, celebration, dancing, and colours: delegates from around 10 ethnicities have come to proudly represent their traditions and identity. Here, the Kachins are instantly recognisable by their red headdress and silver breastplate. There are the Lisus, who is dressed in a deep and unique blue fabric. Further on, there are the Was ethnic group, dressed for war in red and black.

In rounds or in pairs, to slow or powerful tunes and to the rhythm of percussion, each ethnic group showcases its history.

A Young Kachin girl in a displacement refugee camp

Myanmar is a mosaic of 135 ethnicities. These people, each hold their own different dialect, beliefs, and traditions. In this way, the Kachins, Shans, Chins, Karens and Mons can be distinguished from the country’s ethnic majority…the Bamars.

The history of Myanmar has been marked by conflicts and underlying mistrust between the Myanmar army and ethnic minorities on the one hand and, between the different ethnic groups on the other.

From the Second World War onwards, the divergent and strategic alliances between the government and those between them only accentuated the divisions already present under British colonisation. In 1945, General Aung San, father of Aung San Suu Kyi and a Burmese nationalist leader, initiated negotiations with the armed ethnic groups that led to the Panglong Agreement in 1947. This was the first step towards Burmese unity, but it was aborted: General Aung San was assassinated a few months later, which led to the revoking of the Panglong Agreement and the beginning of guerrilla warfare between ethnic groups and the Burmese government.

In 1962, a young military takes over power and increases the Bamar domination of ethnic minorities until 2011. The revolts are repressed, the control is total. Confronted with this military and political leadership, some ethnic groups agree to stand down, while others decide to support Aung San Suu Kyi’s democracy movement. Today, the Myanmar ethnic landscape is still fractured. The Bamar of the mainland and the ethnic minorities, mainly in the border areas, live together moderately well.

Most ethnic groups are spread over the border areas.

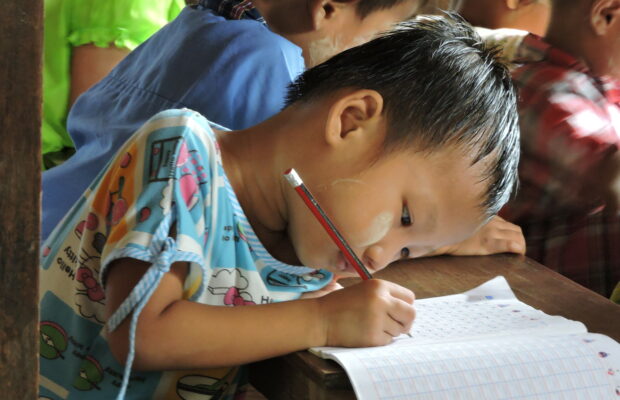

If there is one thing that strikes you when you are with the Burmese, it is their pride in belonging to their ethnic group. A young Shan woman will not wear the same long (traditional long skirt) as a Karen, just as Kachin schoolchildren will not go to school with the same bag as Akha schoolchildren. You might think that at school, Myanmar, the official language, would bring them together and erase their differences, but in fact, dialects prevail, and children continue to speak their mother tongue in the playground. Myanmar is also a foreign language for them, with some young people speaking the official language so poorly that it is a real obstacle in their education.

Within families, dialects are most widely used, while Burmese is a foreign language.

Aside from the purely educational aspect, interethnic groups can be formed and cause rivalries. To face up to the problems, some heads of educational institutions have obliged students to speak Burmese between them. The goal: to help them integrate, improve their prospects and encourage mixing with other students as a way to find out new things.

Conversely, some leaders are eager to preserve the cultural and traditional heritage of their ethnic group. This is the case of one foster home leader who houses around twenty young girls from the Lisu ethnic group: “It is important that they continue to speak the Lisu dialect among themselves, that they learn the traditional songs and dances and that they know their history. It is up to us to preserve our identity.”

Through their coloured costumes et dances, each ethnic group can showcase their history.

This divide between national unity and ethnic diversity is particularly marked in the political opinions and the relationship that populations have with the reigning government.

In the north of the country, among the Shans and the Kachins, the mistrust of the Tatmandaw, the Burmese army, is evident.

Civil wars, drugs, displacement, corruption… In these two states, the humanitarian and economic situation is incredibly difficult, especially in the east of Shan State, the gateway to the Golden Triangle near the Thai border. The inhabitants are cautious when they talk about the Burmese government: straight faces lowered voices. “The government controls everything, even the press. The only thing you can believe in the newspaper is the date,” says a community leader.

A Jingpaw musician in Myanmar

This mistrust is so strong that it is nurtured and passed on from generation to generation. “In the future, I will be a soldier in the KIA (Kachin Independence Army), to kill Burmese,” says a young boy, without batting an eye. We are in Myitkyina, capital of Kachin State; one of the states with the most refugee and internally displaced people (IDP) camps in the country, a direct consequence of the civil conflict. Here, people boycott the visits of the Chancellor, Aung San Suu Kyi, who is seen as a puppet of the government, designed to appease the West.

Distrust is much less pronounced in Chin State; a remote, mountainous area in western Myanmar. The Chin’s do not have land rich in resources like their northern neighbours (minerals in Kachin State or opium in Shan State). As a result, Chin State has long been neglected by governments and is now the least developed state in the country. The remoteness of the villages and the ethnic fragmentation have never allowed the Chins to stand together against the Bamar’s oppressive majority.

The authorities’ lack of interest in them has led to an ethnic indifference to power games. However, the Chins remain hopeful that the policies of Aung San Suu Kyi, who has a reputation for sanctity in this mountainous region, will allow them to prosper. Today, 70% of this neglected group live below the poverty line.

Kachin dancers in Myanmar

In Shan State alone, there are about ten different ethnic groups, each claiming territory and controlling trade. In the IDP camps and villages, people no longer try to find out where the bombs come from. It is the conflict itself that is blamed, especially as each family must produce a child soldier, regardless of age. So, fathers volunteer to keep their sons out of the army, and hostels take in young people to protect them from armed groups.

This mistrust is also rooted in the relationship between the rebel groups and the Tatmandaw, where ambiguity still reigns. “According to the press, the army boasts of impressive drug seizures. But it is the army that is the first to benefit from these drugs! “ rebukes a young Akha.

In Chin State, ethnic groups often have control over the electricity and water in a village. Sometimes, relations with the population are cordial and the leaders of these groups visit the youth hostels and donate rice. Other times, the groups turn against their own population. For example, members of the Student-Chin Front, who are opposed to the government, have burst into villages, helping themselves to provisions in the homes, ordering villagers to carry their belongings and not hesitating to shoot them if they refuse to comply.

Despite the realities of their different lives, there is one thing that these ethnic groups have in common: A future full of doubts. In the areas of populations that have been tarnished by ethnic conflicts for decades, very few belief in a possible peace: The multiple cease-fires over the years have ended in failure. There are some who remain hopeful but know that nothing will change unless their mindsets change too. “We must no longer think of ourselves as separate ethnic groups but as a nation”, maintains an NGO President from the Kachin minority – stuck between resignation and hope. “We must also direct our hate towards the military. They are the only manipulating pieces in all of this”

Jingpaw singers in Myanmar

Whether they be of Chin, Kachin or Shan ethnicity, there are some young Burmese who finish school prematurely to help their parents in the fields. Others take up weapons to join their elders in the ethnic conflicts. In the hope to bring in money for their family, some are ready to risk their lives in mineral extraction mines whilst others give their all to go abroad where, as refugees, they work in factories or plantations for a salary barely more than what they would earn in Myanmar.

The current situation in Myanmar is more than complex – ethnic minorities are torn between a political crisis, increasing poverty, drug and human trafficking […]

It is a real challenge for children in Tedim to go to school. This child sponsorship is a unique opportunity for these children to […]

The Nam Khai programme supports the education of children who live in an isolated rural region plagued by armed conflict, drug trafficking and human […]

Sponsor a child from Myanmar

The Kyauk Tan centre, located east of Yangon, caters to children from communities that live on the margins of development. One-third of the children […]