Fight School Drop Out in Shan State, Myanmar

The current situation in Myanmar is more than complex – ethnic minorities are torn between a political crisis, increasing poverty, drug and human trafficking […]

The 1st of September, 2021 marked the halfway point of the year-long “State of Emergency” declared by the Myanmar military amidst its seizure of government control earlier this year. The deposing of State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi – described by both Myanmar-based and international actors as a military coup – flew in the face of December’s dramatic General Election result, which many had heralded as a new step in Myanmar’s democratic journey. Moreover, the coup put a halt to a long and enduring movement towards equal rights for women in Myanmar and, in particular, equal access to education for women and girls.

Prior to the takeover, long-established norms of gender inequality were being eroded by an active network of women’s rights organisations such as the Women’s League of Burma and the Gender Equality Network, as well as by women such as MP Shwe Shwe Sein Latt in the state’s prominent institutions. In 1997, the country acceded to the Convention to Eliminate all forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). Women’s rights, including the right to education, remain enshrined in Myanmar’s constitution and 17% of MPs elected in the country’s November parliamentary elections were women. In 2012 over 80% of postgraduate students in Myanmar were women and in 2013, the state legislature even launched a National Strategic Action Plan for the Advancement of Women. Though men continue to dominate the labour market, – with women’s participation in 2020 amounting to 48.4% as opposed to men’s 81.9% – women and girls in Myanmar had started to find their voices. As early as 2015, a group of 2,000 young people signed up for an initiative led by US not-for-profit Girl Determined aimed at connecting girls in Myanmar and training them to participate and thrive in society. In 2017, the national government announced funding for the new Department of Alternative Education, intended to bolster non-formal education and literacy training across Myanmar and to address the geographical and cultural divides impeding education around the country.

The junta empowered in February’s coup, which claimed Aung San Suu Kyi’s election victory was the result of electoral fraud, is already showing signs of seeking to roll back such progress. The fact that the bulk of the country’s academic staff are women means that women’s rights and the state of education in Myanmar are inextricably linked: the new government’s reversion to a comparatively tiny budgetary allocation for health and education, and the “hypermasculine” military culture of the government itself, are bad signs for progress at the state level. In addition to this, the time since the coup has seen a heavy military presence in schools themselves, with a number of teachers and academics arrested on suspicion of sympathising with the ousted government. The Prevention of Violence Against Women law (PoVAW), introduced as a bill in early 2019 after years of advocacy by women’s groups such as the UN Gender Theme Group, is now feared to be dead in the water as the incumbent government’s priorities shift away from protecting victims and survivors of domestic violence.

Perhaps of even greater concern is the return of a hawkish government policy on the country’s internal conflicts: the UN has repeated its concerns that conflict-affected women and girls in Myanmar have been subjected to human trafficking and forced marriage, as well as the prevalence of violence against women and girls in rural communities by members of the armed forces. The administrative upheaval that immediately followed the Coup brought greater uncertainty to the thousands already displaced by conflict in Myanmar; in turn, this exposed a gulf in access to safe living and learning conditions for displaced boys and girls. Increased needs specific to women include violence against women and girls exacerbated by the dislocation and consultation in respect of sexual and reproductive health issues.

When women are removed from the peace process, the necessities of half the population are removed from consideration: an opinion poll conducted in Yangon by the Shalom Foundation found 71% of Burmese women surveyed to believe that men cannot fully articulate women’s needs and concerns in a conflict resolution situation. When the same principle is applied to girls and future generations, the long-term needs of the country’s women are neglected even further. Though studies show that nearly 80% of girls in Myanmar attend primary school, the overwhelming majority do not go on to complete secondary school; if the country’s longstanding internal and political conflicts are to be resolved, an uptick in girls’ education is critically important. At 18%, the proportion of Burmese girls that graduate is the lowest in all of Southeast Asia. In addition to the continued incorporation into the learning process of CEDAW provisions surrounding equality and non-discrimination, the UN has recommended temporary constitutional measures to better enable the development of women as leaders in Myanmar. The cultivation of secure and gender-sensitive professional and learning environments for both students and academic staff is essential to the education of a generation of girls able to participate in the peace process; as is allocating funding for gender-conscious care and development and teacher training from the primary school level upwards. However, none of these measures can succeed without sufficient community engagement in education, particularly in respect of migrants, refugees and families displaced by the country’s ongoing military disputes. Women’s traditional roles as home-builders and carers place them naturally at the centre of this community engagement, but the existing curriculum largely fails to cover the peace process or community governance. The integration of non-traditional and formerly inaccessible vocational training into girls’ education in Myanmar should therefore not be viewed as peripheral or secondary to conflict resolution but instead as a central part of bringing peace to both men and women around the country.

The current situation in Myanmar is more than complex – ethnic minorities are torn between a political crisis, increasing poverty, drug and human trafficking […]

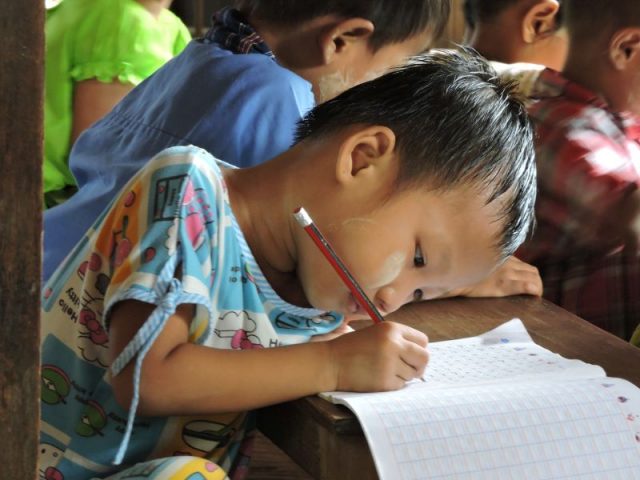

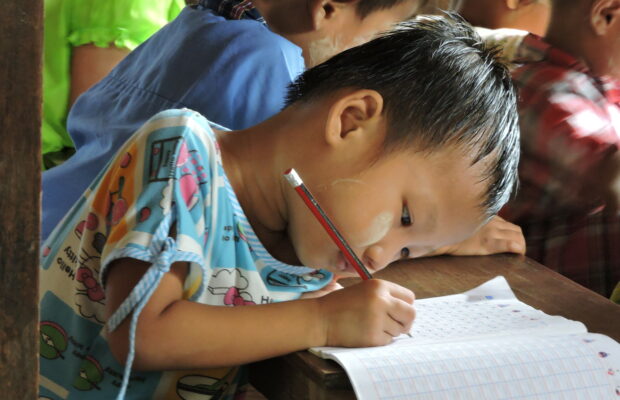

It is a real challenge for children in Tedim to go to school. This child sponsorship is a unique opportunity for these children to […]

The Nam Khai programme supports the education of children who live in an isolated rural region plagued by armed conflict, drug trafficking and human […]

Sponsor a child from Myanmar

The Kyauk Tan centre, located east of Yangon, caters to children from communities that live on the margins of development. One-third of the children […]

The new anti-migration policy in Thailand and the civil war in Myanmar have thrown the border area into turmoil. Faced with the horror from […]

Author: Shi Xian Conflict aftermath in Myanmar poses extensive barriers to quality education for refugee girls, disrupting access due to fleeing families and limited […]