Brighter Tomorrow: Help the children of Babag, Philippines

In the mountains of Cebu, child sponsorship has the power to send children to school safely and encourage them to chase their dreams.

Sponsored children: 0 of 13

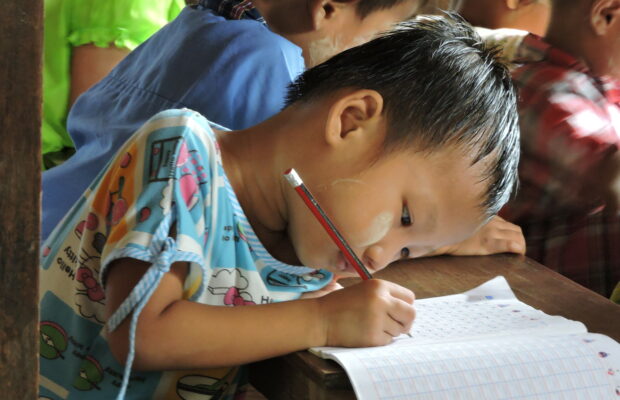

As reported by UNESCO, some 258 million children did not attend school in 2018. The majority of them were female. In Myanmar, 574 334 school-aged children were not enrolled in primary school in 2010, of whom 300 852 were girls. Only 37% of Cambodian women reach upper secondary school. Although multiple reasons exist and often are intertwined, poverty, assigned gender roles and traditions, early marriage, forced and domestic labour, human trafficking and hygiene are some of the most pressing issues preventing girls from accessing education.

Poverty and its multiple facets are the primary reason why girls do not receive formal education. As reported by the United Nations Development Program, a significant portion of the Southeast Asian population still lives in poverty: 37.2% of Cambodians, 23.1% of Laotians and 38.3% of Burmese cannot meet their basic needs.

Given such poverty rates, education is a luxury for numerous families. When parents struggle to provide basic goods and put food on the table, education is often inaccessible. In Myanmar, for instance, the courses taught by teachers are insufficient for students to complete education. Due to their low wages, teachers provide most of their lessons in the form of private after-school courses. It has become a necessity to attend such classes for students to succeed and pass exams. As a consequence, many families cannot afford to provide an education to their children.

Attributed gender roles and patriarchist tradition also significantly impact young women’s educational opportunities. Men tend to have the dominant position, and women are subordinated; women’s roles are to care for their home and be child-bearer, while men are the breadwinners. Education can be considered an investment, one that fits the male gender role and a young man’s future entrance to the workforce and the place he will hold within the family upon adulthood. Therefore, there is a greater inclination among many families to spend money on their sons’ education. Girls are thus left behind; school is not the proper preparation for their future life and is devalued.

The Mekong region is not exempted from such reasoning. Although noting a progression towards more equality, the OECD still underlines in its 2021 SIGI report that intra-household discrimination is consequent. Governments in the region have been pushing for more inclusion of women, but the deep-rooted family traditions are difficult to change. As a result, perceived gender role continues to erect barriers to girls’ education, particularly when it comes to access higher education.

Early marriage is another factor impacting young women’s access to education. Apart from being a local tradition among several ethnic groups, or the hope among certain parents to offer their daughters a brighter future, early marital union is also closely correlated with poverty. Low-income families often seek to marry off their daughters as a coping strategy. The cost of raising a child is high and marriage lifts the burden. Besides, paying bride prices is still a relatively common practice in countries such as Vietnam. In other cases, marriage can be used to settle debts and financial disputes. Thus, there is a strong financial incentive for parents in need to marry off their daughters early, rather than to educate them formally.

What is more, once they become wives, young women are expected to take care of their households. Thus, if they were lucky enough to be enrolled in school before their wedding, they most likely will terminate their education once wedded. Additionally, early marriage is often a corollary to early pregnancy. Becoming mothers further reinforces life-bearer, caretaker roles for girls and makes them statistically more likely to put a premature end to their education, as compared to girls who are solely married.

Early marriage impacts a significant share of female youth in Southeast Asia. Per a UNICEF report, within the countries where Children of the Mekong is deployed, between 11% (in Vietnam) and 35.4% (in Laos) of girls are married before they reach 18 years of age. As a further illustration of the interlinkage between poverty and early child marriage, in 2015, nearly half (43%) of Laotian girls from minority groups and rural regions that are tremendously affected by rampant poverty were wed before they turned 18—a figure well above the national average of 33%. Similarly, the number of early pregnancies is substantial. While the world average adolescent birth rate is 50 per 1000 females aged 15 to 19, it is as high as 94 in Laos and 57 in Cambodia.

Human trafficking and sexual exploitation affect young girls in Southeast Asia disproportionately. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime estimates that the victims of trafficking within the region are predominantly female (26% are young girls, while 51% are women over 18 years of age).

Family financial vulnerabilities are often used as leverage to convince, deceive or coerce families into entrusting their children to traffickers. Recruiters manipulate families or the victims themselves by promising fictitious jobs to the children. Others are put into trafficking through debt bondage, a practice consisting of sending children to work for the creditor to pay off the family’s debt.

Whatever the cause may be, an important number of girls are taken away from the normal life they should lead into the world of human trafficking every year. In the region, places in Thailand and Vietnam infamous for their sex tourism perpetuate the demand for human trafficking. The majority of forced labour in Southeast Asia is classified as sexual exploitation. Once victims are entrusted to their traffickers, their lives are reduced to mistreatment and abuse.

Child labour is yet another impediment to education. Within the Asia-Pacific region, over 60 million children are plagued by the problem. The National Child Labour Survey assessed that in Vietnam alone, over a million children between 5 to 17 years old were engaged in some sort of labour. In Cambodia, 44.8% of children aged between 5 and 14 years old are estimated to be working, as stated in the Cambodia Child Labour survey. Although boys outnumber girls in economically active work, girls are significantly overrepresented in domestic labour—which constitutes a significant share of the overall work by children.

Child domestic labour is a barrier to girls’ schooling. Young women helping their family by contributing to household chores and assisting their mothers is the norm, one that fits the role attributed to their gender. Such tasks are often performed in place of education. Because of women’s role in most Asian societies, many parents judge these chores to better prepare their daughters for their future lives. Yet, this domestic work is far from being limited to merely helping at home. Girls are often expected to seek outside employment and forego formal education in order to improve the family’s meagre income. Wealthier families frequently employ children from poor backgrounds. The figures presented in the International Labour Organization (ILO) report on child domestic labour in Asia and South East Asia further exemplify the scope and impact of domestic work among young women. Indeed, the large majority of those child domestic workers are girls: 97.7% in Hanoi, 87% in Ho Chi Minh City, 77.4% in Bangkok, 82.2% in the Philippines, and 58.6% in Phnom Penh.

While it is true that young boys are also involved in domestic labour, gender plays out much differently in this particular segment of work. More girls than boys in domestic work tend to work full-time. In Cambodia, the overwhelming majority (85%) of boys engaging in domestic work devote 1 to 4 hours doing so daily, while most young female domestic workers must work over 4 hours daily. This is directly associated with educational opportunity: 67.7% of young male domestic workers are still able to attend school, but this figure drops to 46.6% for young women. Ergo, full-time domestic labour does not permit young girls to be on school benches.

Hygiene, or the lack of it, also impedes young women’s education. Access to clean, private, safe and separate facilities is crucially important, particularly during menstruation. The absence of proper sanitation is highly related to absenteeism among female students. In addition, the stigma surrounding periods as a source of shame for young women further impacts their school attendance. In the Mekong region, most schools do not have adequate lavatories that provide girls with the comfort they need to manage their menstrual cycle. In the Philippines and Cambodia, only 39% of schools have adequate accommodations. Students missing school days each month is known to lead them to drop out altogether.

The pandemic and successive governmental policies put into place to mitigate its propagation have further impeded educational access among girls. Indeed, the pandemic has only exacerbated all of the barriers limiting access to schooling for girls. The current crisis has greatly aggravated the economic distress faced by a significant number of families. For the first time in over 20 years, child labour has increased, as the UNICEF and the ILO have warned. Human trafficking has seen a similar increase. Child marriage and early pregnancies have also peaked. Young women in Southeast Asia have not been spared. Hence, COVID-19 did not simply halt the progress made in recent years but has worsened girls’ educational opportunities in the region.

Learn more about our privacy policy here.

By joining our sponsorship programme, you can offer a girl the opportunity to access a school in one of our countries of action. Cambodian, Laotian, Burmese, Philippian, Thai, and Vietnamese girls are still affected by a number of barriers preventing them from filling classrooms. With £28 a month, you will offer a girl schooling, provide her all the necessary school supplies, and ensure she is being fed.

Your sponsorship will help bridge the gender education gap.

In the mountains of Cebu, child sponsorship has the power to send children to school safely and encourage them to chase their dreams.

Sponsored children: 0 of 13

In the small town of Liboro, Philippines, sponsorship has the possibility of transforming the lives of young people by sending them to school.

Sponsored children: 11 of 13

In this neglect community not far from Bangkok, sponsorship is vital in supporting the basic needs of families, enabling their children to attend school. […]

Sponsored children: 11 of 14

In this isolated region in the north of the country, it is difficult if not impossible for the poorest families to send their children […]

Sponsored children: 14 of 15

The current situation in Myanmar is more than complex – ethnic minorities are torn between a political crisis, increasing poverty, drug and human trafficking […]

Urban poverty is appalling in the Philippines. Sponsor a child today and give them the chance to get out of poverty thanks to the […]

It is a real challenge for children in Tedim to go to school. This child sponsorship is a unique opportunity for these children to […]

The Nam Khai programme supports the education of children who live in an isolated rural region plagued by armed conflict, drug trafficking and human […]

Sponsor a child from Myanmar

The Kyauk Tan centre, located east of Yangon, caters to children from communities that live on the margins of development. One-third of the children […]