Fight School Drop Out in Shan State, Myanmar

The current situation in Myanmar is more than complex – ethnic minorities are torn between a political crisis, increasing poverty, drug and human trafficking […]

Poe Ta Hay grins, revealing a few reddened fragments of the betel he’s been chewing all day and sits on his heels. He’s taking a break in the surrounding jungle. Here in the heart of Karen State in southeast Burma, the villages are extremely isolated and have no roads nearby. They are accessed via paths that cross the jungle or via rivers. Even motorbikes can’t be ridden on the steep mountain slopes, and most villagers like Poe Ta Hay have to walk for many miles between villages.

Poe Ta Hay left his village of Toe Thay Dern this morning. “Kawthoolei is the Karen name for our State, he explains, chewing his betel. The KNU (Karen National Union, the political organization that the Karen National Liberation Army gave rise to) is in charge of this region”. Karen State is an exception in Burma. The area has always been a hostage of the brutal civil war that completely transformed the local political organization and the attitudes of the people. Considered at the end of the 20th Century to be the longest-running civil war, the Karen guerilla conflict ended in 2012 with a historic ceasefire. Karen State was granted political independence from the majority of the State’s rural areas. In exchange, the government and the Burmese army agreed to maintain the management of the major roads in Kawthoolei and all essential communication infrastructures.

Poe Ta Hay looks down on a sea of vegetation from the top of the mountain that overlooks Hpapun province (Mutraw, in the Karen language). The mountain separates the villages of Toe Thay Dern and Lay Nar Dern. Mist reveals the depths of the valleys. It’s hard to imagine what life is like underneath this canopy of green. Here and there, however, signs of life have left traces. A pond of dried mud abandoned by buffalo, elephant droppings, and plastic bags. The living jungle hides the regular comings and goings of people and animals.

Relationships are of critical importance in this green and lush environment. The villagers have always known this and work to strengthen their lines of communication. In Lay Nar Dern, Poe Ta Hay is welcomed with open arms. He knows almost everyone among the twenty or so village families, even though Lay Nar Dern is a six-mile walk from his village. He lodges with a longtime villager during his visit. “I’m used to walking from one village to the next to visit the schools”, he explains. Poe Ta hay works in a clinic near the Thai border. He’s also responsible for coordinating the network of community schools (CSP) put in place by Eh Thwa Bor, providing access to education for children living in isolated villages [see box below]. For the last few years, the KNU has gradually taken on more responsibility regarding daily life in the State and has opened a number of village schools. “We must all work together, Eh Thwa confides, it’s the key to success. I’m happy to accept the KNU leaders’ guidance if it means that children can go to school”.

Eh Thwa was born in Hpapun in Karen State, the second of 5 children. Since 2001 she’s devoted all her free time and energy to building and financing small community schools in Karen villages abandoned by the central government. “Back then, many children escaped the war and found sanctuary in the forest. Sometimes they even made it their home”, she explains simply, as proof of why she chose this particular work. “There was nothing for them in that hostile environment. Someone had to do something”. Today, Eh Thwa is in charge of a program of 33 community schools. Altogether, more than 3,000 children have access to education thanks to her network of 180 teachers spread throughout Karen State.

How to govern a mass of villages that resemble little islands embedded in a woodland sea? The question of independence is far from a simple one. Everything has to be organized, not just the schools, but the hospitals as well. Nyunt Win, who we came across at Lay Nar Dern on the back of a motorbike, is responsible for setting up medical aid throughout Hpapun province. He coordinates the work of 19 clinics primarily equipped to deal with malaria, dysentery, and the severe bouts of diarrhea that strike villagers. “Fortunately, cases like these are no longer common. We’ve almost been able to eradicate these illnesses in the last 10 years”.

Nyunt Win speaks fast. He’s in a hurry. He has enormous responsibilities, and yet he’s not paid for his work. The KNU pays him in the form of sacks of rice, enough to meet the basic needs of his family. Political engagement within the KNU is seen as a patriotic one, in the same way, that military engagement is, and it’s been that way for a long time.

Volunteers take on major responsibilities in central Karen State. Village men able to assist their communities are identified and asked to serve. “I was asked if I wanted to work for the KNU and I said yes. I was sent to train at the Mae La refugee camp in Thailand. I trained as a health care worker at the Mae La medical center before returning home. Initially, I was in charge of one of the clinics, then I coordinated all the health services for the province”. A CB radio in the house crackles and spits out a few words, and Nyunt Win pauses to respond. His daughter plays with a mobile phone nearby but the network doesn’t cover the whole region and shortwave is still the best way to communicate in the area.

On the surrounding mountain tops and in the villages however it’s common to see young people glued to phone screens powered by a few basic solar batteries. The Internet has been part of life for a while now in the area although the network is incomplete due to the irregular terrain. So for better or worse, the villages are increasingly in contact with the outside world.

Karen territory is still full of anti-personnel mines. Nyunt Win responds to the radio request and is off to a workshop specializing in prosthetics in the Day Bu Noh military camp. Independence requires preparing for the future of course by focussing on education and health, but it also calls for healing the wounds of the past. After nearly 50 years of civil war, the region is far from unscathed. Many dangerous areas remain due to the number of mines set by both camps. Stories abound of farmers leaving one morning to work in their fields only to step on a mine. Fear of these mines is one of the most common reasons preventing refugees in Thailand from returning home. Here in Burma, the villagers have a different perspective, though. It’s simply an extension of the state of war: despite the 2012 ceasefire, in reality, nothing has been resolved. Years of guerrilla warfare have shaped the Karen people’s view of their own political identity as an identity of opposition. Lay Hay fought for the KNLA for 14 years. He left the army in 1995 but his 19-year-old son has been in the KNLA for over a year. “We are not free yet, he explains. The two armies are preparing for war again. We signed a ceasefire agreement but we still don’t have peace! There are still areas where fighting is going on in Karen State such as Ler Mu Plaw and Kyaw Mu Plaw” [see the question below]. This constant state of tension prevents the villagers from believing in the possibility of peace. It’s perhaps the greatest obstacle to the success of the KNU’s project for independence because building a meaningful and long-lasting political project takes time. The independence won by the KNU is only temporary in the eyes of villagers like Lay Hay. Very few Karen people living in the most isolated villages in Hpapun province believe in lasting peace. The army travels all over the region and when the villagers, in the course of a conversation, mention the Burmese, they describe them as ‘enemies’. Even today, every family must give up one of its sons to fight for the KNLA. Parents often have to choose which child they will be. They see it more as a necessary choice as opposed to a painful one. “Karen State is ours and we have to control it ourselves. And our sons are helping us do that” Lay Hay tries to explain.

The villagers still feel a sense of fear, despite their resignation. Today’s relative stability and Burma’s changes in politics haven’t made a difference. Lay Hay, like all the other villagers, are afraid of what the future might bring. The Karen people are certain of having won a battle but they don’t know what the outcome of the war will be. Unfortunately, both the militarisation of Karen State by the Tatmadaw (the Burmese army) and the violation of the ceasefire in March give reason to their fears. Lay Hay insists however that ‘the Karen people want peace: It’s always better than being at war!’ He smiles a smile coloured red by betel and adds as if embarrassed by the truth he’s about to reveal, “because if there was to be another war, we’d have to leave our homeland once again”.

The current situation in Myanmar is more than complex – ethnic minorities are torn between a political crisis, increasing poverty, drug and human trafficking […]

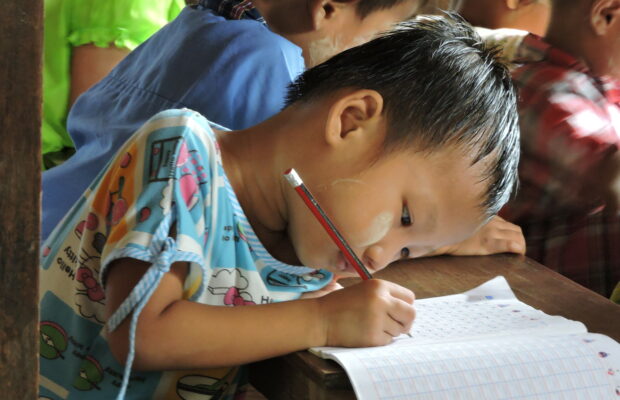

It is a real challenge for children in Tedim to go to school. This child sponsorship is a unique opportunity for these children to […]

Sponsored children: 24 of 31

The Nam Khai programme supports the education of children who live in an isolated rural region plagued by armed conflict, drug trafficking and human […]

Sponsor a child from Myanmar

The Kyauk Tan centre, located east of Yangon, caters to children from communities that live on the margins of development. One-third of the children […]